In 1988, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which included a section on “Preventing Drug Abuse in Public Housing.” It required public housing authorities to include new rules in their leases that terminated a lease if the tenant, a member of their household, or a guest engaged in any “drug-related criminal activity, on or near public housing premises,” including drug possession and use.

Everyone should have access to stable, affordable housing, but many people are denied places to live based on misguided ideals of deterring people from using or being around drugs. This twisted drug war logic ignores the fact that denying housing or kicking people out of their homes only creates new problems and makes existing ones worse. People and families without homes are less likely to be able to keep jobs or stay in school, and those without homes who are using drugs are more likely to overdose or use more chaotically. Instead of shutting people out, we should be opening doors so that everyone has a place to call home. Drug use shouldn’t sentence someone to living on the streets.

The drug war has its roots spreading throughout our lives, blocking people from a foundational aspect of healthy lives: a stable place to live. It’s still spreading — and we can do something about it.

The Roots of the Drug War Go Everywhere

Housing Insecurity Is Deadly

The drug war has seeded ineffective and inhumane housing policies on drug use, which make it possible for landlords to evict people who use drugs. Eviction increases the risk of overdose death and causes homelessness. These policies hurt people and do not make communities stronger or healthier.

Eviction increases the risk of overdose death and causes homelessness

Federal “One Strike” policies for public housing authorities encourage immediate eviction after suspected drug activity. Eviction does not require an arrest or criminal conviction — it doesn’t even matter whether the drug use is otherwise non-problematic. Once someone has been evicted for drug-related activity, federal law requires housing authorities to ban access to public housing for three years, though authorities in at least 12 states impose even longer bans. Tens of thousands of people have lost their homes due to these misguided policies.

Tens of thousands of people have lost their homes due to these misguided policies

Facing much stricter rules than they would in private housing, an entire family can be kicked out of public housing if one family member is even suspected of using drugs — even if the family member does not live in public housing themselves. These policies have forced many people onto the street and put many families in the impossible position of choosing between giving up housing or turning their backs on family members who would make the entire family ineligible for assistance by using (or even being suspected of using) drugs.

An entire family can be kicked out of public housing if one family member is even suspected of using drugs

Private landlords have bought into the drug war logic by denying leases to people with criminal convictions, including drug convictions. There are very limited protections against discrimination based on a record or prior arrest, meaning landlords have the ability to deny housing based on often old and irrelevant information — with nearly half of landlords in one survey saying they would reject housing applications from those with a criminal record. Because drug war enforcement has disproportionately targeted people of color, discrimination in private housing closes options to people who have been most impacted by the drug war.

Discrimination in private housing closes options to people who have been most impacted by the drug war

Dig deeper to see how these systems are connected.

Even though Emily Ramos’ father, Emiliano Ramos, had lived in public housing in New York City all his life, when he completed his prison sentence for selling marijuana, he was barred from returning to his home. The New York City Housing Authority had a rigid rule that denied housing to people convicted of drug-related crimes, even if they were otherwise eligible. A felony drug law violation is one of the few offenses that can temporarily or permanently lock someone out of public housing, leaving people unhoused or unstably housed and making it more difficult to get a job, maintain relationships, and rebuild their life.

Emily Ramos

New York, New YorkThe Drug War Grows Unchecked

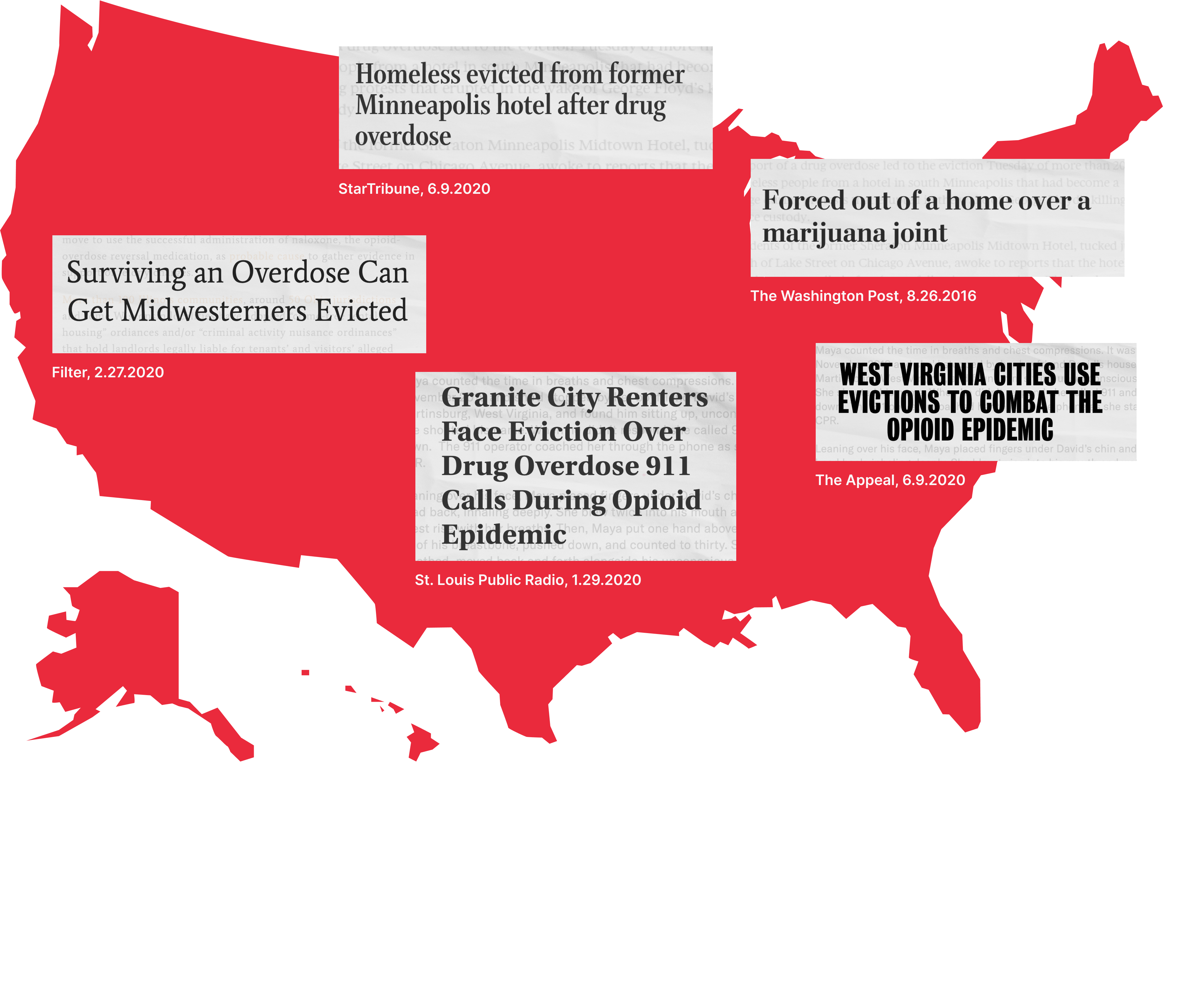

Across the United States, there are increasing accounts of landlords evicting people who overdose or people suspected of drug use or activity, even if landlords are not explicitly mandated to do so. These evictions can come without a drug arrest or conviction.

In New York City, a drug-related arrest, even one that does not result in a conviction, is enough to trigger eviction or permanent exclusion from public housing.

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) can terminate the tenancy of any resident who engages in drug-related activity on or even near a housing project. Eviction proceedings can be initiated before charges are even determined, and once a person’s name is on the permanent exclusion list, it’s almost impossible to get the ban lifted. More than 5,000 people are permanently excluded from NYCHA housing. In some cases, even young people under the age of 18 can be excluded.

Pull the Drug War Up by the Roots

The drug war has forced families from their homes and prevented people from finding stable housing for at least three decades. These cruel policies have only harmed health and safety and increased costs to the public. We should focus on making sure everyone has a stable place to call home, regardless of whether they use drugs.

We Should:

We can uproot the drug war from our communities.

It Takes All Of Us

Get involved in the grassroots movement to uproot the drug war in all systems.