When Ronald Reagan announced his modern war on drugs, the idea that schools should aggressively police drug use became a focal point of his presidency.

That idea has blossomed into an education system that is so obsessed with stamping out the presence of drugs or any real conversation about them that it’s blocking young people from fully participating in school and laying the groundwork for future harms. We care for our children when we prioritize their health and well-being, but the drug war has warped our ability to provide the real support our children need.

Schools should be safe and caring environments, not vehicles of policing and stigmatization. Young people who show up to learn are often subject to invasive bag and locker searches or drug tests before they can participate in school activities — regardless of whether there’s any real suspicion they may be using drugs, much less any evidence to justify these violations of privacy. Drug education is failing in the U.S., as abstinence-only prevention approaches have left generations of young people unprepared to reduce their risk of harm if they do choose to use drugs. From elementary school to college and beyond, students who have been cited for using or selling drugs have been blocked from receiving financial aid and participating in student activities, which are crucial stepping stones to success for young people.

The drug war has its roots spreading throughout our lives, criminalizing our students and invading our places of learning and growth. It’s still spreading – and we can do something about it.

The Roots of the Drug War Go Everywhere

Disastrous Prevention Efforts

The “Just Say No” education campaign, Drug Abuse Resistance Education (D.A.R.E.), and other federally-funded drug education efforts of the past five decades have all preached abstinence-only and zero tolerance, which neither reduce the harms of drugs nor keep young people safer. These prevention programs make drug use out to be a matter of personal morality and responsibility, shaming people for youthful curiosity and experimentation and spreading fear and biased, inaccurate information. Unshockingly, moralistic, anti-drug programs like D.A.R.E. have not led to a “drug-free America” or even drug-free schools. Evidence clearly shows that they have been ineffective, unlike harm reduction-based education programs that have been proven to work, like DPA’s Safety First curriculum.

anti-drug programs like D.A.R.E. have not led to a “drug-free America” or even drug-free schools

Beginning in the 1980s and 1990s, locker searches led by security officers and canines, increased suspensions and expulsions, and other means of keeping tabs on kids became the norm. Drug use is now the second-highest source of student referrals to police. And despite no evidence that police presence in schools improves safety or reduces drug use, the number of officers grows every year. Nationally, 10 million students are in schools that have law enforcement officers but no social workers. Scaring kids with severe punishments and expanding police presence break trust between students and the adults they should be able to turn to at school if they need help or resources. It drives the small percentage of students who actually do use substances problematically further into the shadows and actually prevents early intervention and meaningful help.

10 million students are in schools that have law enforcement officers but no social workers

Over one-third of school districts randomly drug test students, with some requiring tests for students as young as 11 years old, despite the fact that drug testing does not reduce drug use. Rigorous studies have not found any evidence that school drug testing programs deter students from drug use or reduce the harms associated with drugs. And, in fact, drug testing can actually exacerbate harms. In many schools, for instance, the consequence of a positive drug test is exclusion from school sports and extracurricular activities, the very activities likely to provide the structure and supervision that facilitates abstinence from drug use.

Tests for students as young as 11 years old

Harsh school discipline or contact with the criminal legal system can have lifelong consequences. Young people who have been policed and disciplined for their purported drug use are more likely to drop out of school. And from 1994 to 2020, there was a federal ban on Pell Grants, a subsidy the U.S. federal government provides for students who need it to pay for college, for incarcerated students. And many colleges require applicants to disclose past criminal histories, which stops potential students from even applying. Black, Indigenous, and Latinx students receive the highest percentages of federal financial aid and are also targeted by drug war enforcement at higher rates. Drug convictions have had a catastrophic impact, especially on the populations most in need of financial aid.

Young people who have been policed and disciplined for their purported drug use are more likely to drop out of school

Dig deeper to see how these systems are connected.

Steven Mangual enrolled in college when he was incarcerated for a drug-related crime at the age of 21, and it was then that he discovered his love of learning. But after successfully completing his first year, his dream of achieving a college degree was thwarted. Congress had just passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 — commonly known as the 1994 Crime Bill — which, among other things, ended Pell grants (i.e. federal student aid) for incarcerated people. Steven was devastated when he found out that the door to higher education and greater opportunity had been slammed shut. Drug convictions are routinely used to deny educational opportunities for people at all stages of their education.

Steven Mangual

Bronx, New YorkThe Drug War Grows Unchecked

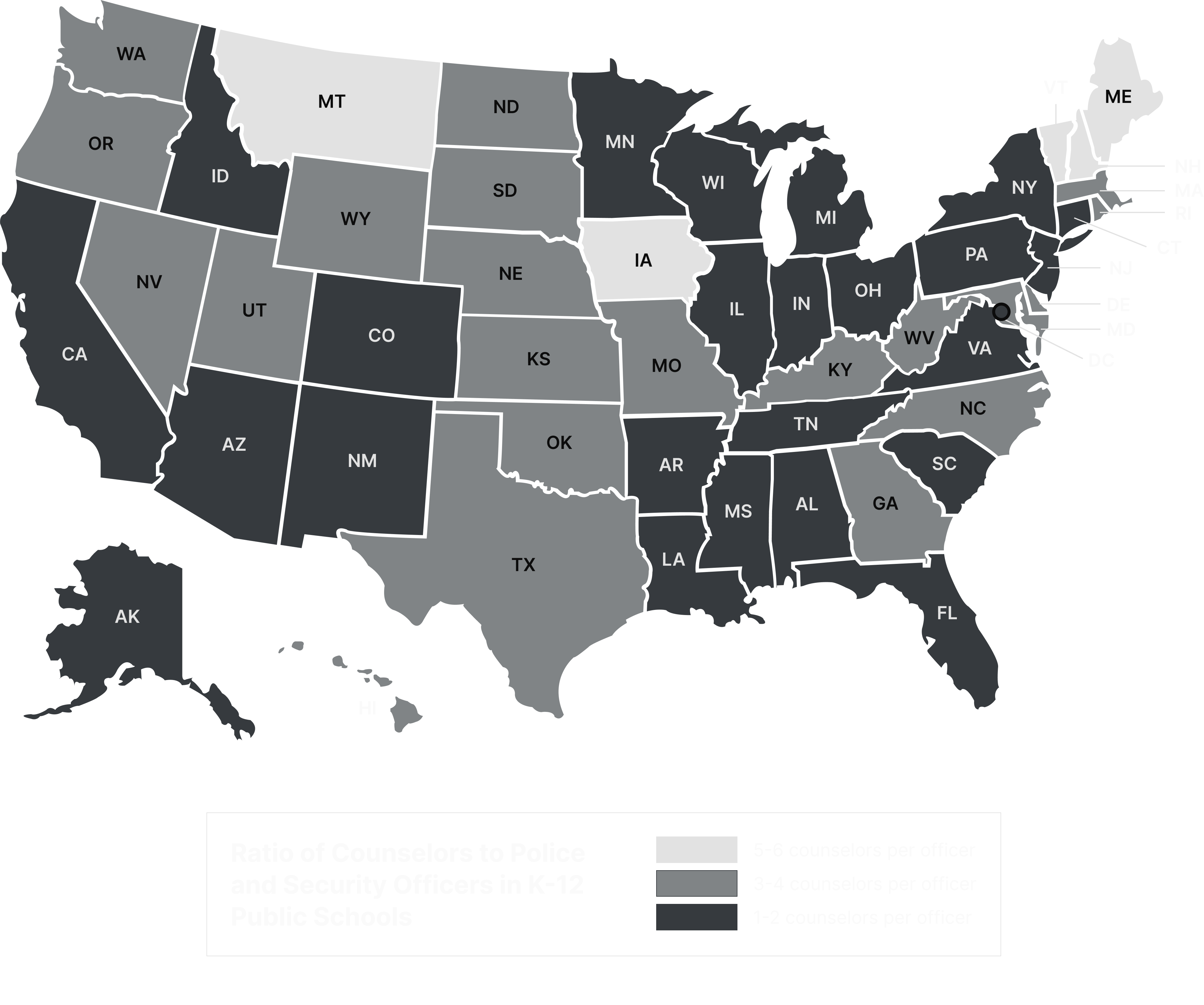

Twenty-four states and the District of Columbia have almost as many police and security officers as they do school counselors. Federal match funding driven in part by the drug war has enabled schools to hire more police and security officers in schools and prioritize staff focused on school discipline over staff working for student well-being.

Random student drug testing results in significantly reduced use of illicit drugs.

A 2013 meta-analysis of 14 years of data from nationally representative samples of middle and high school students found that random student drug testing among the general high school student population was actually associated with “moderately higher use” of all illicit drugs other than marijuana.

Pull the Drug War Up by the Roots

Schools should be places for learning and support. Focusing on drug enforcement and punishment creates an adversarial relationship between students and administrators. Denying education to students for drug use, particularly students of color, leads to increased unemployment, income inequality, costly health problems, and incarceration.

We Should:

We can uproot the drug war from our communities.

It Takes All Of Us

Get involved in the grassroots movement to uproot the drug war in all systems.