Starting in 1973 with the passage of the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), and continuing with the escalation of the drug war in the 1980s, real and perceived drug use has been used as an excuse to remove children, primarily children of color, from their homes and communities.

Under the drug war logic that has infiltrated our child welfare system, any drug use is equivalent to child abuse, regardless of context and whether or not there is actual harm to the child. This has resulted in formalized policies that demonize parents, testing them for drugs (often without their consent), relentlessly investigating them, and routinely removing their children without any reason other than supposed drug use. Even though research shows that children have the best outcomes when they are able to remain with their parents, our child welfare system uses the same punitive approach that plagues our criminal legal system. Choosing to punish rather than help results in a host of negative impacts on families and children.

Too many families have been torn apart because of stigma, misunderstanding, and the lack of supportive services caused by the drug war. The drug war has its roots spreading throughout our lives, sapping the life from our communities. It’s still spreading — and we can do something about it.

The Roots of the Drug War Go Everywhere

Rhetorical attacks by lawmakers and pundits on low-income Black women and their children were relentless during the 1980s and 1990s, which led to a huge increase in child removal proceedings and foster care placements across the country. From 1982 to 2003, federal funding for removing children skyrocketed over 20,000% with no increases in funding for support services for families. Drug war logic has directly led to a system of surveillance and punishment of mothers of color, reinforcing the wrongheaded and racist view that the child welfare system is better suited to care for children of color than their own families.

Federal funding for removing children skyrocketed

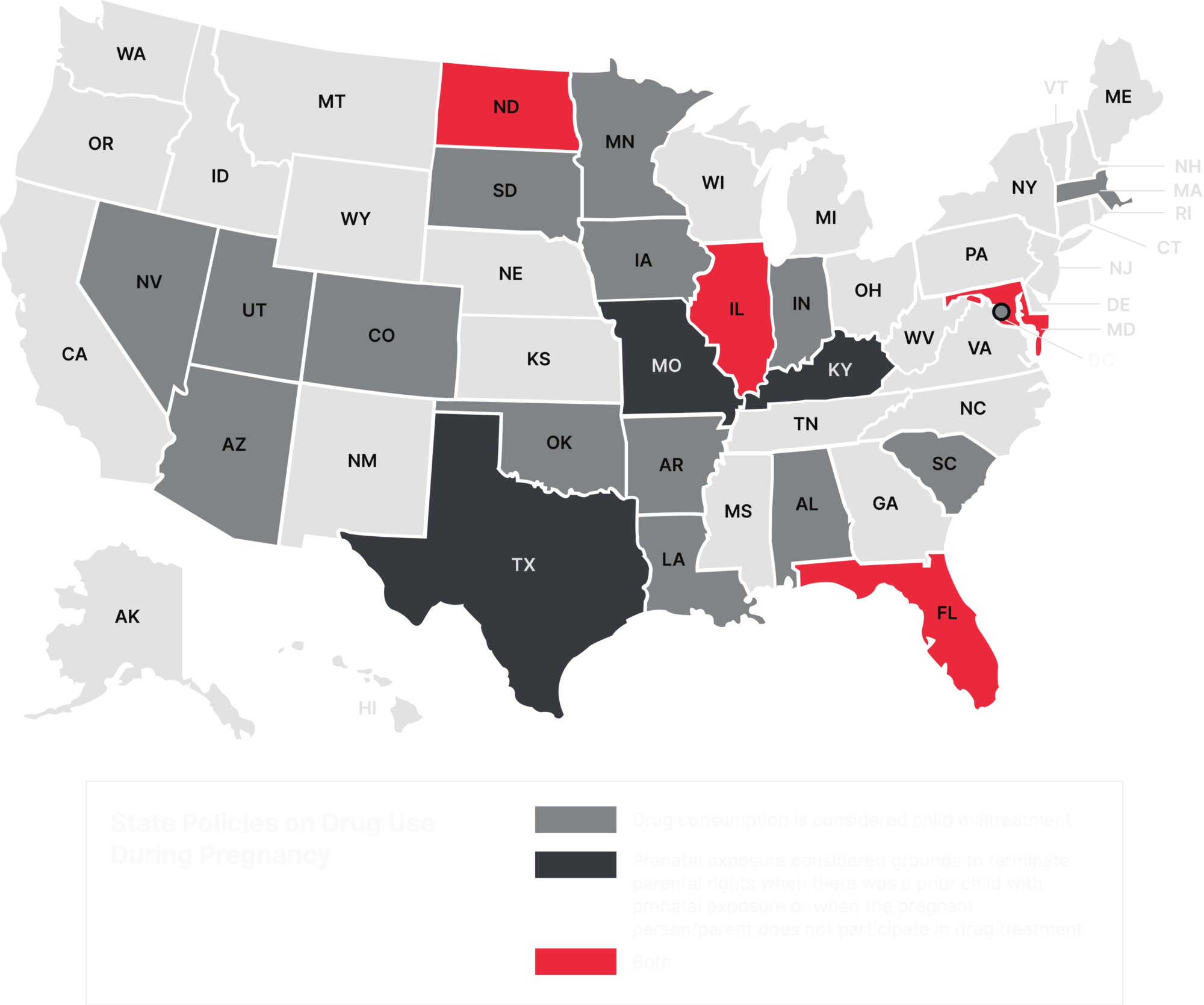

Pregnant people, especially low-income people of color, are routinely drug tested, often without their consent. These tests, both during and after pregnancy, have been used as a tool to punish parents and families, despite the fact that a drug test does not indicate whether or not someone is a good parent. Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have laws that consider any drug use during pregnancy to be child maltreatment. Unsurprisingly, this can lead to removal of children born to parents who used drugs during pregnancy, even without signs of harm. And fear of these tests can cause pregnant people to avoid healthcare altogether.

A drug test does not indicate whether or not someone is a good parent

Increased Investigations

Drug use has become one of the most prevalent allegations in child maltreatment investigations, but the connection between drug use and supposed inability to care for children is not supported by evidence. Some studies estimate that over 80% of all foster system cases involve caretaker drug allegations at some point in the case. Over one-third of removals in 2016 involved allegations of parental alcohol or other drug use as a contributing factor — a 17% increase from the turn of the century and the largest increase of any reason for removal in the last five years, despite relatively stable rates of drug use among the population.

the connection between drug use and supposed inability to care for children is not supported by evidence

A positive drug test can be used as justification to mandate parents to abstinence-based drug treatment, even when a person does not have a substance use disorder. People who are receiving care need to feel like they have a trusting relationship with their provider. Mandating treatment is counterproductive and can result in unintended negative outcomes that are detrimental both individually as well as to the family unit. Substance use disorder treatment should be held to the same ethical standards as the treatment of other health conditions, where provision of services without informed consent is considered highly inappropriate.

People who are receiving care need to feel like they have a trusting relationship with their provider

Dig deeper to see how these systems are connected.

Despite no evidence of abuse or neglect of her children, Elizabeth Brico’s parental rights were terminated in 2020. She had previously been in treatment for an opioid use disorder and was in remission at the time of the trial. Her previous drug use, along with a groundless complaint by her in-laws, led to the loss of custody of her two young daughters — the beginning of a nightmare from which she has not yet emerged. The stigma and bias against parents who use drugs in the child welfare system unnecessarily ripped her family apart.

Elizabeth Brico

Seattle, WashingtonThe Drug War Grows Unchecked

Nineteen states and the District of Columbia define prenatal exposure to drugs as sufficient evidence to make a finding of child maltreatment. Seven states consider prenatal exposure grounds to terminate parental rights when there was a prior child with prenatal exposure or when the pregnant person/parent does not participate in drug treatment.

People have been charged with assault with a deadly weapon for using drugs while pregnant.

The moral panic around crack cocaine in the 1980s and 1990s led to extreme punishments for pregnant people. During the late-1980s more than 200 criminal prosecutions were initiated against mostly people of color in close to 20 states. The charges included assault with a deadly weapon (i.e. crack cocaine), felony child neglect, and endangering the welfare of an unborn child. These types of prosecutions continue today.

Pull the Drug War Up by the Roots

The drug war has provided the means to justify removing children from their families. Placing the blame on individual parents and drug use offers an easy scapegoat that detracts from focusing on structural issues like racism, poverty, and lack of supportive services.

We Should:

We can uproot the drug war from our communities.

It Takes All Of Us

Get involved in the grassroots movement to uproot the drug war in all systems.